The Islamic State doesn’t overthink things, but there is a group that is particularly bothersome for them: the Copts. The two videos of executions in Libya have shown the death of Copts: first, Egyptian Copts in February, and now, Ethiopian Copts in April.

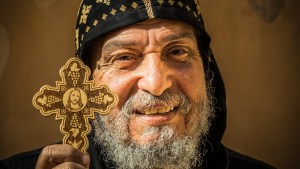

The Copts are a tiny Christian minority in the Near East. They are martyrs: they die for their faith. They traditionally tattoo a cross on their wrist. They are an example of how, in Muslim-majority countries, it is possible for Christians and Muslims to live side by side. That’s why ISIS kills them. They are troublesome.

Aleteia interviewed Fernando de Haro, a professor at the Francisco de Vitoria University in Madrid, who is also a writer and a journalist. He has studied the life of Copts in Egypt today; he has even lived with them. The fruit of this experience is his book Copts:A Journey to Meet the Martyrs of Egypt (Encuentro Publishers).

—What personal motivation led you to study and document the Copts in Egypt?

I had been in Egypt at the end of the 80s with a group of friends. We traveled the country from north to south for a month. We made many friends among the Copts (Egyptian Christians). Accompanied by some students from the Jesuit college in Cairo and by some young professionals, we submerged ourselves in a little-known world. On long trips, during dinners that lasted until dawn, during visits to monasteries, to the homes of the rich and the poor, we had the opportunity to take part in some way of the life of the Copts.

Those Christians, who use the language of the Pharaohs in a liturgy passed down from the first centuries of Christianity, fascinated us, children of the purist European rationalism.

It bothered us that they saw us as travelers full of romanticism, using our vacation to engage in a bit of superficial Eastern tourism. We had a different goal. We wanted to be with the people. And the fact that a sense of mystery—something that had so often been denied us—unfolded before our eyes so richly, made us love Egypt.

In 2011, there was a major attack against one of the churches in Alexandria, shortly after Mubarak was forced out of power. And I wanted to return, to do an in-depth report, to answer the questions that afflicted me: Would the Copts still be there? It was clear that they were, because the news spoke about them—about dozens of deaths and attacks; about their suffering, their protests, and their change of patriarch. But would they continue to exist as a religious people within the Egyptian nation? And what I have found is that people die for their ideals.

—The Copts are one of the most threatened—and poor—minorities. Why?

There are poor Copts and rich Copts. Most are poor, and some are very poor. Up until the 70s, they lived as Christian minorities usually do in countries with a Muslim majority: with limited freedom, but freedom.

But starting in the 70s, an important change takes place. Sadat needs to reach out to the most Islamist sectors of society—Islamist, not Islamic—and begins to discriminate against the Copts more systematically. In this period, we see the first attacks against churches.

Christians have been part of the project of constructing the Egyptian nation. They participate very clearly in the process of independence and the development of modern Egypt. But in the last three decades of the last century, they begin to suffer a significant reduction of their rights. Together with the regime’s increasing closeness to Islamism, another economic phenomenon takes place. Egyptians migrate to Gulf countries, and when they return, they bring with them a kind of discriminatory behavior that is contrary to Egyptian tradition.

And the situation doesn’t improve with Mubarak

During Mubarak’s long rule, the situation worsens. At first, Mubarak is not especially harsh with them, although he doesn’t permit them to build or repair their churches. But towards the end, Mubarak is nefarious, because he comes to a tacit agreement with the Muslim Brotherhood, which at that time has grown significantly. This non-aggression pact consists in permitting the Muslim Brotherhood to attack Christians with almost absolute impunity.

In 2011, during the first revolution, in Tahrir square and for a brief period of time, Muslims and Christians are together again. But the Muslim Brotherhood takes control of the revolution and returns to attacking the Copts. Until the Muslim Brotherhood is removed from power by the people in June of 2013, the Copts are harshly attacked. Attacked by the Muslim Brotherhood while they are in power, attacked by the Muslim Brotherhood when they are the opposition. Since Al Sisi has become president, things have gotten slightly better.

—Egypt is the only country, besides the Holy Land, where Jesus walked. How do the Copts experience that presence?

Devotion to the Holy Family is present everywhere. Surely, not only because the Holy Family visited these lands, but because the Copts have been exiles in their own country for centuries.

Coptic culture has created stories that have no pretensions of historicity, and which are still repeated today. They belong to a very oriental genre. They are delicious stories that emphasize how important the events they relate are for the lives of Mary, Joseph and Jesus.

One of these stories from the 7th century relates that when the Holy Family stopped alongside the road, and Mary wanted to eat some dates which she couldn’t reach, the Child Jesus ordered the palm tree to bend down. The angels took a branch from that palm tree to plant it in paradise. The tree that grew from that cutting is the one that all the saints see first when they enter heaven.

The first conversions are supposed to have taken place when the Holy Family passed through, such as those of Klum and Sarah, who gave them refuge; or that of Titus, an unscrupulous bandit whom Egyptian tradition identifies with the Good Thief. Mary, Joseph and the Child Jesus are accompanied on their journey by the woman who had been the Virgin’s midwife: Salome.

Copts: The word comes from the Greek word “Aigyptos.” They are a group of Christians native to Egypt. They make up about 10 percent of the Egyptian population. The majority belong to the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria and to the Catholic Coptic Church. They are underrepresented in the government. They seek to maintain good relations with the authorities and always are vocal about praying for peace, peaceful coexistence, and interreligious dialogue.

Read more:

5 Things to know about Coptic Christians