As the 50th anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor approached in 1991, an official from the Japanese foreign ministry forestalled any possibility that Japan’s Parliament would do anything to memorialize the event. The end of the Second World War had brought deep humiliation to the Japanese Empire, and a commemoration would just bring out so much pain.

The foreign ministry official shut down all debate by simply stating that all those who had been involved in the attack on Hawaii were now dead, thus implying that the subject was not worthy of discussion.

As far as many Japanese citizens were concerned, those who took part in the attack — and indeed, anyone who served in the military at that time — might as well have been dead. They either ignored or shunned the veterans, according to Marcus Perkins, a photographer who has written about Pearl Harbor.

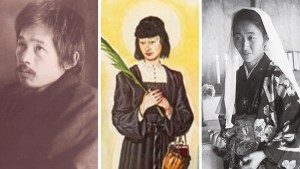

But some of these veterans were very much alive — not only not cowering in humiliation, but finding ways to turn that humiliation, shame and regret into something life-giving. One such was Takeshi Maeda.

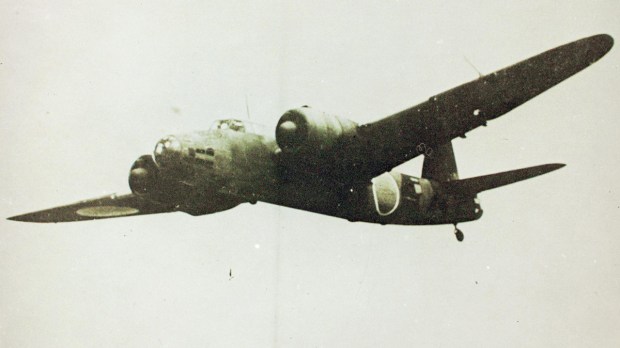

Born in 1921, Maeda joined the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1938. Three years later, after training for an attack on a place he knew nothing about, his plane took off from an aircraft carrier in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, carrying a single torpedo. His was one of 350 aircraft that would swarm over Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. In their wake, they would leave over 2,330 Americans dead and numerous ships sunk or badly damaged.

The torpedo Maeda dropped, along with torpedoes from nine other planes, sank the battleship West Virginia.

Maeda served for the duration of the war, and the long tenure gave him a chance to change his views about the conflict. As Perkins writes, “In August 1945, he was forced to join the ranks of the Kamikaze pilots’ Special Attack Force. ‘I had accumulated 3,800 hours of combat flying experience. I couldn’t believe my commanders wanted to waste all that in a single mission,’” Maeda said. Perkins explains:

It was at this point that he first realized the fallibility of his leaders and the recklessness with which they had treated the lives of the Japanese people. It is an opinion he has held ever since. He feels the Americans’ decision to use atomic weapons against Japan was in revenge for the attack on Pearl Harbor. However, he believes that ultimately it resulted in the saving of more Japanese lives than were lost; the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki led Emperor Hirohito to urge his people to surrender on August 14, just two days before Maeda was due to make his Kamikaze flight.

Working for reconciliation

After the war, Maeda ended up laboring quietly for a large Japanese corporation. Eventually, he began working to develop the relationship between Japanese and American veterans of Pearl Harbor, and became a member of the Japan-US Cultural Exchange Committee, writes Jennifer Popowycz the Leventhal Research Fellow at The National WWII Museum.

The same year the foreign ministry official persuaded the Japanese Parliament to ignore the 50th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Maeda gave a speech in English at a symposium for the US Pearl Harbor Association in Hawaii. The speech ended with the simple but strong words “Pearl Harbor — never again.”

He had brought a group of Japanese veterans with him and attended the opening of the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum.

Maeda continued to have encounters with American military veterans who had survived the attack — his former enemies — and pursued initiatives to promote peace and understanding. Two others who took part in the attack — Zenji Abe and Kaname Harada — did likewise.

Efforts not in vain

In 2006, Maeda performed a “handshake reconciliation service” with a survivor of the USS West Virginia, Popowycz points out. She quotes him to describe the event:

“So there I was, rather unexpectedly, and everything is lit up and wired for sound and it was in that situation that for the first time in my life I meet, face to face, my counterpart from the American side. They told me that he was a crew member of the West Virginia, and so the first thing I said was, ‘I’m very sorry.’ I’m sorry because you know, here I am, someone who had sunk this man’s ship, and of course he’s standing [there] as a survivor …But his answer was, ‘Well don’t be sorry, you don’t have anything to be sorry about.’”

“The man shaking Maeda’s hand was John Rauschkolb, a Navy signalman, who … had to swim under burning fuel to escape bullets being fired at him from a Japanese Zero fighter,” Popowycz writes. “In an interview after the event, Rauschkolb stated ‘I’ve never held anything against them. They were doing their job. I was doing my job. We were military. They were taking orders. I was taking orders.’”

She continues:

As part of his reconciliation efforts, Maeda also made many close American friends, several of whom were on the West Virginia the day he helped sink it. “I was able to develop a relationship with some of my American counterparts. The sailors, the crews, on the US Navy ships during the Pacific conflict, a lot of these people became friends of mine.” Richard Fiske, for instance, was a Marine bugler aboard the West Virginia and, after meeting Maeda, the two became close friends, visiting each other regularly until Fiske’s death in 2004.

During one visit to Japan, Maeda presented Fiske with a medal on behalf of the Japanese government for working as his counterpart in facilitating understanding between United States and Japanese veterans. By commemorating annual anniversaries at Pearl Harbor and developing friendships, veterans on both sides actively engaged in forgetting past tensions, creating a new way to remember the war based on peace, understanding, and absolution.

When Maeda died at the age of 98 in 2019, hewas the last surviving Japanese airman directly involved in the attack on Pearl Harbor. His efforts, though, have not been in vain. In 2016, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe traveled to Pearl Harbor on the 75th anniversary of the attack. Standing at the USS Arizona Memorial with then-President Barack H. Obama, Abe said, “I offer my sincere and everlasting condolences to the souls of those who lost their lives here as well as to the spirits of all the brave men and women whose lives were taken by a war that commenced in this very place and also to the souls of the countless innocent people who became victims of the war.”