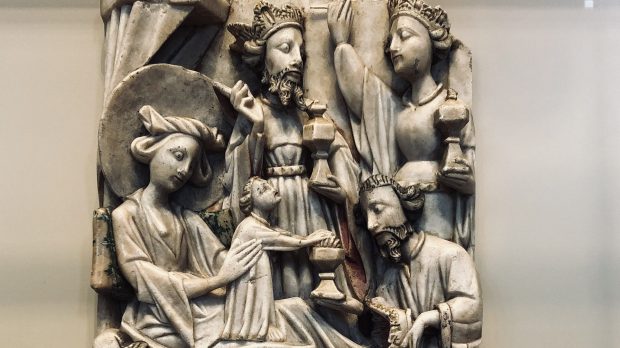

By now the Three Kings of Orient would have been heading home after visiting the infant Jesus. Their clothing and appearance in this alabaster sculpture are very English – at a time when other artists were depicting the multicultural origins of the Magi. Within a few decades, European art would feature African-looking kings as well as a profusion of Eastern turbans.

If the Three Kings were from Persia, which seems likely, they would certainly have wanted to take some fine English alabaster back with them. For millennia throughout West Asia this was the preeminent material for sculpting sacred images. England was a late-comer to the field, but when it got going in the late Middle Ages, this remote island created an unbeatable brand for itself. The smoothness and ethereal glow of the English stone shone through, even when smothered with paint and gilding.

This example from the early 15th century has lost most of the decoration that covered it originally. The fine-grained gypsum known as alabaster is so soft, it’s a wonder that the detail has remained at all. The English carvers used all the local fashions – and children’s hairstyles – of the time to create a charming scene that is entirely remote from reality and yet universally popular. There are records of English wares reaching most of Europe, but so far no confirmed sightings in the Middle East.

It’s just as well so many were exported as large quantities were destroyed by iconoclasts in Britain. The alabaster carvers of Nottingham and elsewhere had to change creative direction after the Reformation. From that point onwards they focused on the less-inspiring subject matter of English noblemen’s tomb effigies.

The virtual Museum of the Cross

The Museum of the Cross, the first institution dedicated to the diversity of the most powerful and far-reaching symbol in history. After ten years of preparation, the museum was almost ready to open; then came COVID-19. In the meantime, the virtual museum is starting an instagram account to engage with Aleteia readers and the stories of their own crucifixes: @crossXmuseum