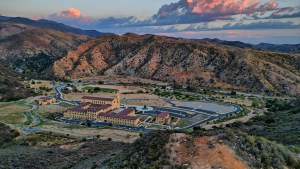

Its silhouette catches the eye of anyone who by train or by road crosses the Susa Pass that separates Italy from France. Often half-drowned in mist or clouds, indistinct but impressive, from below it looks like a fortress planted there since time immemorial to guard the access to the Alpine passes. And it is indeed a fortress, even if its role for more than a millennium has been to fight evil powers rather than human invaders.

A strategic location

In Roman times, the Empire was aware of the strategic interest of Mount Pirchiriano: from its 3,081 ft of altitude, it dominates Piedmont and watches over, along with the Fréjus and Mont Genèvre passes, the road to Gaul and the Via Domitia, an irreplaceable land link between Italy and Spain. Rome built a guard post there. This stronghold is 19 miles from Augusta Taurinorum, the modern Turin.

History doesn’t record clearly whether the Roman legionaries were stationed up there, in surely uncomfortable conditions, or were ever called into action there, since the true perils that would lead to the collapse of Roman power would pass along other roads. What is certain, however, is that the place was abandoned little by little without losing its strategic importance: at its feet passes the Via Francigena that lead travelers, pilgrims and merchants from France to Rome.

Perhaps this is the reason why Brother Giovanni Vincenzo, a Camaldolese religious from a new community of hermits founded by the future Saint Romuald of Ravenna, settled not on Pirchiriano but on a peak facing it, Monte Caprasio. Thus he could when called upon help those who needed it. It would be an ephemeral lodging. One night in 980, Brother Giovanni was suddenly awakened by an impressive presence: the archangel Michael himself had descended from Heaven to instruct him to erect a shrine on Pirchiriano in his honor.

The Archangel Michael’s request

Giovanni knew better than to joke with the Prince of the Celestial Militia or to take his orders lightly. He could get angry when people don’t comply quickly enough. Bishop Lorenzo of Sipontium, in Apulia, renamed “Manfredonia” in the Middle Ages, experienced this bitterly in 492, as did Aubert of Avranches in the Cotentin region in 706. Both were late in building the shrines the archangel had requested on Mount Gargan and on the islet that would become Mont Saint-Michel — and they would pay for it. Giovanni was cautious, and would not debate the order or procrastinate.

The only difficulty – and it was a big one – is that a poor hermit has by definition no money, nor the worldly connections that would allow him to get any.

In spite of everything, and with the little he had, the good Camaldolese set to work and, for want of anything better, built an oratory in the place chosen by the Archangel who, as we know, loves the tops of mountains – if only to upset the devil (honored in these places under the name of Lugd, Mercury or Wotan) by taking his place. Having done his best, Giovanni escaped the reprisals suffered by the two bishops before him.

But then, a few months after this apparition, a rich lord from Auvergne, Hugues de Montboissier, went to Rome with his wife, Isengarde. The 10th century was tumultuous in France, for lack of a real power to bring order. While waiting for Hugues Capet, in 987, to impose himself on the throne at the expense of the last discredited Carolingians, the out-of-control warrior nobility imposed its own law, or rather its tyranny, on peoples without a protector. These feudal predators were capable of all kinds of turpitude, and of all kinds of crimes, and the clergy didn’t always have the courage to condemn their conduct.

The aristocrat from Montboissier, for his part, had transgressed all the limits and incurred excommunication. Thus, his confessor had sent him to Rome to obtain pardon from the pope. As he returned to France – sincerely repentant, it seems, because faith did not desert tormented souls at that time – the Piedmontese lord who offered him hospitality spoke to him of the oratory of Brother Giovanni, and of the Archangel’s requests. St. Michael was dear to the Frenchman and, in a burst of generosity, Hugues de Montboissier undertook to build the requested shrine with his own money. The work began in 983.

Benedictines from Auvergne

What emerged was an improbable construction between heaven and earth: San Michele della Chiusa — St. Michael’s Abbey. It’s a masterpiece of the Romanesque period, famous among other things for its prodigious Staircase of the Dead, which was given its unique name because the great figures of the abbey were buried alongside it. The stairway leads to the famous “Door of the Zodiac.”

The whole, of an austere beauty, will perhaps seem strangely familiar to you. This is not surprising, at least if you are a movie buff. San Michele, like the French shrine to the same archangel, inspired the setting of the palaces of Gondor in The Lord of the Rings, a story full of Catholic references that tells of a terrible struggle between the powers of evil and the forces of good, an obvious echo of the battles of the Second Coming. Let’s add that San Michele was also the inspiration for the setting of a less edifying novel, The Name of the Rose, by Umberto Eco.

For seven centuries, the Chiusa was home to a Benedictine abbey – one of the richest and most powerful in Europe, linked to Cluny – with the peculiarity of only receiving monks from Auvergne, according to the wishes of its founder. These close ties with France explain why San Michele had many priories in France that contributed to its glory.

Decline

This good fortune had an end. In 1622, eager to put an end to abuses that had been reported, Rome closed the abbey. It remained abandoned for 210 years, beaten by snow, wind and fog, doomed to almost certain ruin. Pope Gregory XVI finally saved it in 1836 by authorizing the Rosminian monks to establish themselves there.

Since then, San Michele has become one of the most popular tourist destinations in Piedmont and is well worth a visit. It’s possible to spend the night in one of the old monks’ cells, now equipped with modern comforts.